paradise valley and

Black bottom, Detroit, mi.

Urban Futures Lecture

“…Indeed, the chance to pioneer, to be part of a unique and significant new community, was, for many, an important factor in deciding to settle there…” (Forum Magazine, 1960)

Urban Futures

Last month, RogueHAA convened the latest panel discussion in its Provocations: Challenging Detroit’s Design Discourse series. Lafayette Park served both as backdrop and case study for a discussion of the broad social, political, architectural, and urbanistic issues that surround this development. Lafayette Park began as an urban renewal initiative known as the Gratiot Redevelopment Project which targeted 129 acres of land within the primarily working class African-American neighborhood of Black Bottom. Between 1946 and 1958, thousands of residents were displaced and the site largely remained vacant until the city retained Chicago-based developer Herbert Greenwald, architect Mies van der Rohe, urban planner Ludwig Hilberseimer and landscape designer Alfred Caldwell to design a plan for redevelopment. By the early 1960’s, three 22-floor high-rises, 21 buildings with 186 ground-level housing units, and a large park were completed. Despite the controversy surrounding its implementation, the Lafayette development has achieved many of the goals of Modernist planning and urban renewal and today is one of the most economically viable and racial diverse neighborhoods in the city.

To this context rogueHAA brought together the following distinguished professionals to discuss the many facets of Lafayette Park:

Danielle Aubert (assistant professor of graphic design, WSU)

Robert Fishman (professor of urban planning, U of M)

Kevin Harrington (professor emeritus, IIT)

Michelle Johnson (executive director, Fire Historical and Cultural Arts Collaborative)

Hilanius Phillips (Former head city planner, City of Detroit)

Brent Ryan (assistant professor of urban design and public policy, MIT)

Optimistically titled Urban Futures, the event addressed both the history of its planning and execution, but also the many paradoxes that accompany one of the more successful of Detroit’s urban neighborhoods. Does Detroit offer similar opportunities for avant- garde planning and large scale urban interventions today? What successes and sacrifices accompany the Modernist social agenda, and are there lessons to be learned as we seek to engage in equitable and sustainable redevelopment here and in other Rustbelt cities? While the presentations and subsequent discussion covered a broad array of topics, there were a number of themes that emerged.

Race & Relocation

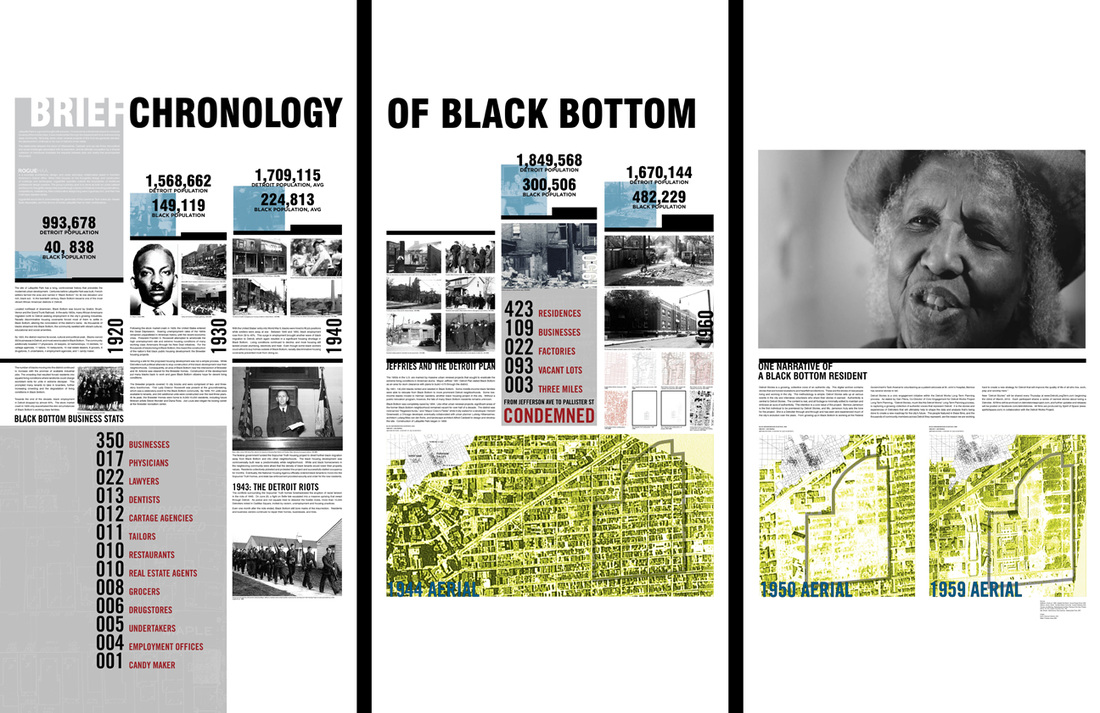

Underlying much of the conversation was the reality of the vast displacement that occurred through the urban renewal process, and the failed relocation strategies implemented by the city leadership. As discussed in rogueHAA’s A Brief History of Black Bottom exhibit, the area was cleared in the early 1950s as part of a campaign to eradicate the extreme conditions in Detroit’s slums. The Lafayette Park development model was based largely on the rejection of the chaos and congestion of the industrial city. From a utopian and socialist agenda, the ‘tower in the garden’ represented a reprieve from the extreme density in these areas. Ironically, by the time the development was implemented the city had already begun to lose population at its center. As described by Robert Fishman(professor of urban planning, U of M), this intentional removal of working class poor was also seen as a way to stem the massive suburban migration that followed World War II by encouraging the middle class to remain in the city. While one of the goals of the project was purported to be better housing conditions for the primarily black, working-class residents of Black Bottom, the other was the buoying of property values and the establishment of a new urban model.

Efficacy & Execution

It took over ten years for the city to condemn 129 acres, relocate 1,950 families, prepare and receive approval for reuse of the land, and ultimately sell the land to developer Herbert S. Greenwald. However, as Kevin Harrington noted, the completion of Lafayette Park came not after the construction of the buildings but the maturation of Caldwell’s landscape design. It is only after the plantings have reached their specified height that the relationships between building and landscape reach their intended potential. This slow fruition makes one wonder in an era used to technological immediacy, how can slow occupations like architecture, and more so urban planning and design, command cultural relevance? How can we provide visible (and timely) measures of success throughout long term processes to maintain public interest?

Paradox & Compromise

The work of Hilberseimer and Caldwell represents two extremes: one of rationalized, scientific planning, the other an aesthetically derived landscape design. Likewise, as illustrated by Danielle Aubert in her studies of current Lafayette Park residents, a paradox exists between the rigid grid of Van der Rohe’s living units and the individual expressions of its inhabitants. The panelists discussed the removal of ornament and socio-historical artifacts in Mies’ design and its ability to both organize space but also potentially establish a more equitable field for human habitation. Likewise, the overall configuration of the living units provides a literal transparency that leads to a visual connectivity throughout the development.

Social Agenda, Market Objectives and the Emergence Post-Modern Planning

The disenfranchisement of the residents of Black Bottom is as much the legacy of Lafayette Park as the development’s success in raising property values and creating a diverse and sustainable community. Such consequences of Urban Renewal precipitated many of the canons of post-modern planning, including participatory measures and relativism. Brent Ryan spoke of the vast shift in the urban design profession from large scale vision toward more targeted, small scale interventions and the challenges that this shift poses. In a city in which capital development is prioritized and incentivized to overcome an anemic market, we must also ensure proper representation by existing residents while still maintaining the financial and creative integrity of a project. Michelle Johnson noted both the need for participatory planning as well as for collaborative efforts between multiple regional communities. Her work fosters these connections by encouraging stronger relationships between community members and the spaces they occupy.

Urban Pioneers

As the opening quote suggests, there was a certain frontierism that accompanied the Lafayette Park development from its very conception. The Park represented a new urban model – an avant-garde approach to living that was distinct from both traditional urban and suburban development strategies. Today, as Detroit embarks on a variety of urban planning endeavors – accompanied by another wave of urban pioneers – it is important to consider both the challenges of Lafayette Park but also the potential of such avant garde vision. It may be possible to implement similar spatial strategies through new materials -as proposed by Hilanius Phillips, and there may be the potential for new urban models altogether, which capitalize on Detroit’s unique conditions to create something visionary.

“…Indeed, the chance to pioneer, to be part of a unique and significant new community, was, for many, an important factor in deciding to settle there…” (Forum Magazine, 1960)

Urban Futures

Last month, RogueHAA convened the latest panel discussion in its Provocations: Challenging Detroit’s Design Discourse series. Lafayette Park served both as backdrop and case study for a discussion of the broad social, political, architectural, and urbanistic issues that surround this development. Lafayette Park began as an urban renewal initiative known as the Gratiot Redevelopment Project which targeted 129 acres of land within the primarily working class African-American neighborhood of Black Bottom. Between 1946 and 1958, thousands of residents were displaced and the site largely remained vacant until the city retained Chicago-based developer Herbert Greenwald, architect Mies van der Rohe, urban planner Ludwig Hilberseimer and landscape designer Alfred Caldwell to design a plan for redevelopment. By the early 1960’s, three 22-floor high-rises, 21 buildings with 186 ground-level housing units, and a large park were completed. Despite the controversy surrounding its implementation, the Lafayette development has achieved many of the goals of Modernist planning and urban renewal and today is one of the most economically viable and racial diverse neighborhoods in the city.

To this context rogueHAA brought together the following distinguished professionals to discuss the many facets of Lafayette Park:

Danielle Aubert (assistant professor of graphic design, WSU)

Robert Fishman (professor of urban planning, U of M)

Kevin Harrington (professor emeritus, IIT)

Michelle Johnson (executive director, Fire Historical and Cultural Arts Collaborative)

Hilanius Phillips (Former head city planner, City of Detroit)

Brent Ryan (assistant professor of urban design and public policy, MIT)

Optimistically titled Urban Futures, the event addressed both the history of its planning and execution, but also the many paradoxes that accompany one of the more successful of Detroit’s urban neighborhoods. Does Detroit offer similar opportunities for avant- garde planning and large scale urban interventions today? What successes and sacrifices accompany the Modernist social agenda, and are there lessons to be learned as we seek to engage in equitable and sustainable redevelopment here and in other Rustbelt cities? While the presentations and subsequent discussion covered a broad array of topics, there were a number of themes that emerged.

Race & Relocation

Underlying much of the conversation was the reality of the vast displacement that occurred through the urban renewal process, and the failed relocation strategies implemented by the city leadership. As discussed in rogueHAA’s A Brief History of Black Bottom exhibit, the area was cleared in the early 1950s as part of a campaign to eradicate the extreme conditions in Detroit’s slums. The Lafayette Park development model was based largely on the rejection of the chaos and congestion of the industrial city. From a utopian and socialist agenda, the ‘tower in the garden’ represented a reprieve from the extreme density in these areas. Ironically, by the time the development was implemented the city had already begun to lose population at its center. As described by Robert Fishman(professor of urban planning, U of M), this intentional removal of working class poor was also seen as a way to stem the massive suburban migration that followed World War II by encouraging the middle class to remain in the city. While one of the goals of the project was purported to be better housing conditions for the primarily black, working-class residents of Black Bottom, the other was the buoying of property values and the establishment of a new urban model.

Efficacy & Execution

It took over ten years for the city to condemn 129 acres, relocate 1,950 families, prepare and receive approval for reuse of the land, and ultimately sell the land to developer Herbert S. Greenwald. However, as Kevin Harrington noted, the completion of Lafayette Park came not after the construction of the buildings but the maturation of Caldwell’s landscape design. It is only after the plantings have reached their specified height that the relationships between building and landscape reach their intended potential. This slow fruition makes one wonder in an era used to technological immediacy, how can slow occupations like architecture, and more so urban planning and design, command cultural relevance? How can we provide visible (and timely) measures of success throughout long term processes to maintain public interest?

Paradox & Compromise

The work of Hilberseimer and Caldwell represents two extremes: one of rationalized, scientific planning, the other an aesthetically derived landscape design. Likewise, as illustrated by Danielle Aubert in her studies of current Lafayette Park residents, a paradox exists between the rigid grid of Van der Rohe’s living units and the individual expressions of its inhabitants. The panelists discussed the removal of ornament and socio-historical artifacts in Mies’ design and its ability to both organize space but also potentially establish a more equitable field for human habitation. Likewise, the overall configuration of the living units provides a literal transparency that leads to a visual connectivity throughout the development.

Social Agenda, Market Objectives and the Emergence Post-Modern Planning

The disenfranchisement of the residents of Black Bottom is as much the legacy of Lafayette Park as the development’s success in raising property values and creating a diverse and sustainable community. Such consequences of Urban Renewal precipitated many of the canons of post-modern planning, including participatory measures and relativism. Brent Ryan spoke of the vast shift in the urban design profession from large scale vision toward more targeted, small scale interventions and the challenges that this shift poses. In a city in which capital development is prioritized and incentivized to overcome an anemic market, we must also ensure proper representation by existing residents while still maintaining the financial and creative integrity of a project. Michelle Johnson noted both the need for participatory planning as well as for collaborative efforts between multiple regional communities. Her work fosters these connections by encouraging stronger relationships between community members and the spaces they occupy.

Urban Pioneers

As the opening quote suggests, there was a certain frontierism that accompanied the Lafayette Park development from its very conception. The Park represented a new urban model – an avant-garde approach to living that was distinct from both traditional urban and suburban development strategies. Today, as Detroit embarks on a variety of urban planning endeavors – accompanied by another wave of urban pioneers – it is important to consider both the challenges of Lafayette Park but also the potential of such avant garde vision. It may be possible to implement similar spatial strategies through new materials -as proposed by Hilanius Phillips, and there may be the potential for new urban models altogether, which capitalize on Detroit’s unique conditions to create something visionary.

Historian wants further search for clues in coal chutes

By DEBRA HAIGHT, H-P Correspondent | Posted: Monday, May 8, 2006 12:00 am

BERRIEN SPRINGS — The historian hired to study coal chutes under downtown buildings has found no evidence to tie them to possible Underground Railroad activity, but another historian wants more research on whether Berrien Springs residents helped escaped slaves.Michelle Johnson, Michigan Freedom Trail Commission coordinator, said she hopes the coal chute investigation will spark interest in more research on the Underground Railroad and other anti-slavery activity in Berrien County. She said it's significant that there were black Americans living in Berrien Springs and Berrien County in the decades before the Civil War. "In every other place, we've seen a relationship between high numbers of African Americans and Underground Railroad activity," she said. "These were places where people felt safe, and I feel strongly that we need to do that research. … I think there could be a very interesting story there." She said she wants volunteers to do more research. For instance, volunteers could study deeds to see who owned downtown buildings and what those persons' backgrounds were. Johnson said she would be willing to help in any effort to learn more about black American history in Berrien Springs. Her organization sponsored a survey of the historic Ramptown settlement near Vandalia a few years ago. The village of Berrien Springs this year hired architectural historian Jeffrey Green, a planner with the city of Monroe, to study the coal chutes. The study was mandated by the Michigan State Historic Preservation Office before the state would allow work to go forward on the village's $850,000 downtown streetscape project. Green toured the downtown in late March, taking samples from the foundations of buildings where coal chutes can still be found. He then researched census records and the history of Underground Railroad activity in Michigan. Green concluded in a report last month that tests showed a strong likelihood the foundations predate 1870. However, he could find no evidence the chutes were used for anything besides coal. "Certainly, evidence may surface at some future point linking an individual property owner, building, basement or coal chute to the UGRR (Underground Railroad) in some way, but that evidence is not present today," he wrote. Diane Tuinstra, an environmental review assistant for the state preservation office, said last week she expected her office to accept Green's findings and allow the streetscape work to continue. The project is expected to start in late August or be held until next spring. It will bring improvements to Main and Ferry streets. Tuinstra echoed Johnson's sentiments. She said similar coal chutes were used for the Underground Railroad in other areas, and she hopes more research will be done.

By DEBRA HAIGHT, H-P Correspondent | Posted: Monday, May 8, 2006 12:00 am

BERRIEN SPRINGS — The historian hired to study coal chutes under downtown buildings has found no evidence to tie them to possible Underground Railroad activity, but another historian wants more research on whether Berrien Springs residents helped escaped slaves.Michelle Johnson, Michigan Freedom Trail Commission coordinator, said she hopes the coal chute investigation will spark interest in more research on the Underground Railroad and other anti-slavery activity in Berrien County. She said it's significant that there were black Americans living in Berrien Springs and Berrien County in the decades before the Civil War. "In every other place, we've seen a relationship between high numbers of African Americans and Underground Railroad activity," she said. "These were places where people felt safe, and I feel strongly that we need to do that research. … I think there could be a very interesting story there." She said she wants volunteers to do more research. For instance, volunteers could study deeds to see who owned downtown buildings and what those persons' backgrounds were. Johnson said she would be willing to help in any effort to learn more about black American history in Berrien Springs. Her organization sponsored a survey of the historic Ramptown settlement near Vandalia a few years ago. The village of Berrien Springs this year hired architectural historian Jeffrey Green, a planner with the city of Monroe, to study the coal chutes. The study was mandated by the Michigan State Historic Preservation Office before the state would allow work to go forward on the village's $850,000 downtown streetscape project. Green toured the downtown in late March, taking samples from the foundations of buildings where coal chutes can still be found. He then researched census records and the history of Underground Railroad activity in Michigan. Green concluded in a report last month that tests showed a strong likelihood the foundations predate 1870. However, he could find no evidence the chutes were used for anything besides coal. "Certainly, evidence may surface at some future point linking an individual property owner, building, basement or coal chute to the UGRR (Underground Railroad) in some way, but that evidence is not present today," he wrote. Diane Tuinstra, an environmental review assistant for the state preservation office, said last week she expected her office to accept Green's findings and allow the streetscape work to continue. The project is expected to start in late August or be held until next spring. It will bring improvements to Main and Ferry streets. Tuinstra echoed Johnson's sentiments. She said similar coal chutes were used for the Underground Railroad in other areas, and she hopes more research will be done.